#Inspiration

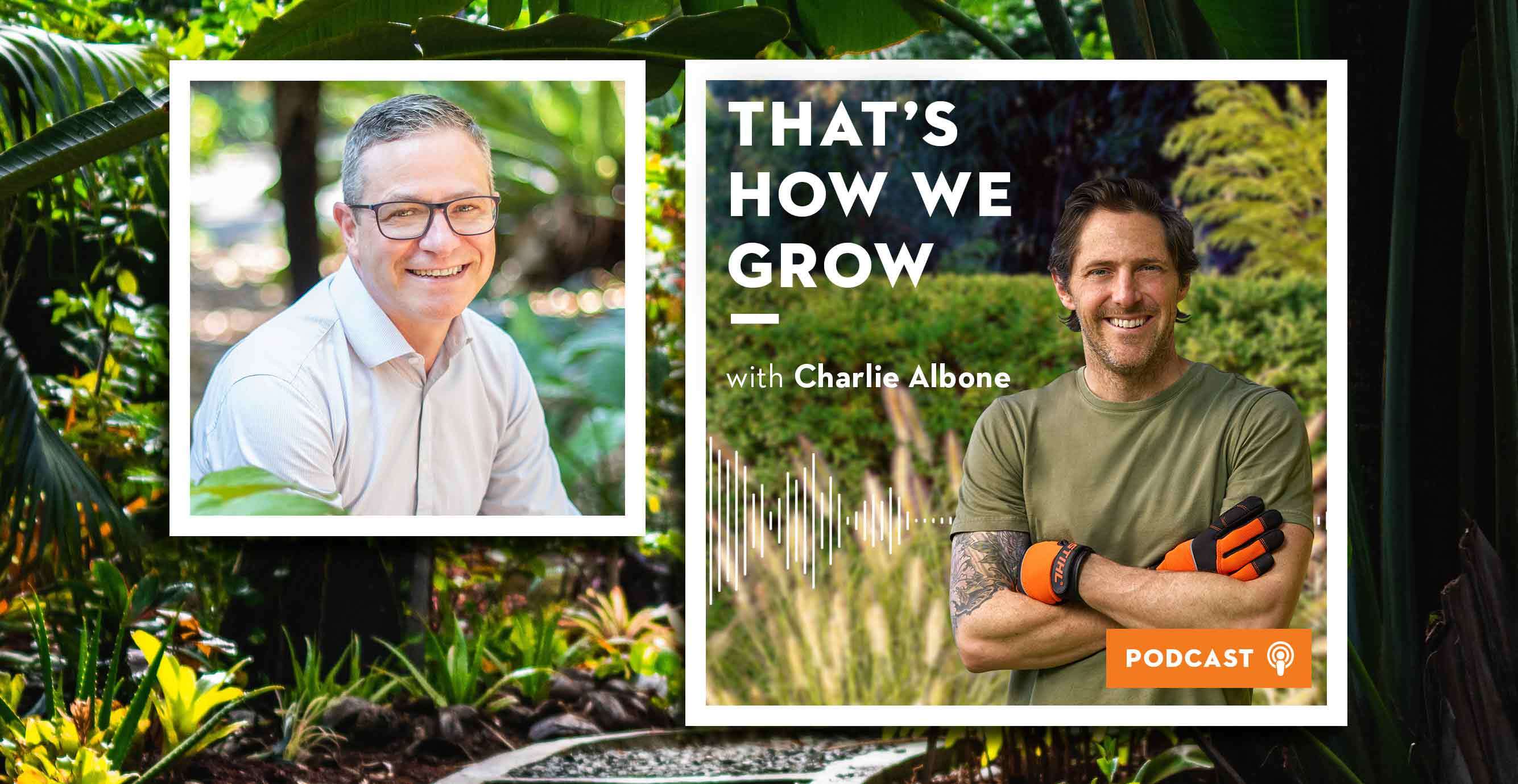

Episode #7: Perfect garden maintenance workflow with David Laughlin

Charlie Albone:

Hi, I’m Charlie Albone and welcome to episode seven of That’s How We Grow in partnership with Stihl Garden Power Tools. Throughout this series, we’ve been looking to provide the best advice to tackle that large gardening project you’ve been putting off. Whether it’s laying or repairing your lawn, preparing a vegetable patch, or pruning your trees. We hope you understand the steps needed to achieve this. Once you have the garden looking great, it’s simply a process of maintaining it. One challenge simply rolls over to another. But it is an incredibly rewarding feeling, being able to sit back and enjoy your garden once all the initial hard work has been done, seeing what you’ve achieved, enjoying it for all it’s worth. Believe it or not, but for some, the maintenance can become laborious, which raises a few questions. How do professionals play and prepare for maintenance? How do you plan to maintain a large garden, particularly an internationally famous city landmark garden.

Charlie Albone:

Well, joining me today will be David Laughlin from the Sydney Botanic Gardens. It’s going to be great to hear from David around how he and his team plan and prepare for the ongoing maintenance of the gardens. For us at the home, our plans are going to be on a small a scale, obviously, but there will be plenty of nuggets for us to learn.

Charlie Albone:

David Laughlin has been with the Sydney Royal Botanic Gardens for over 10 years, and he is the curator manager. Like me, he has an interest in perennial borders, annual color, and has a love for the Australian [inaudible] family. David, welcome.

David Laughlin:

Hey.

Charlie Albone:

Can you tell us a little bit about your horticulture career please. And how on earth did you arrive at the Sydney Botanic Gardens?

David Laughlin:

Well, Charlie, I guess I started as every good horticulture as should with an apprenticeship and I was lucky enough to get an apprenticeship at the Royal Botanic Gardens. It was a bit of a career change for me so I was quite an elderly apprentice when I started and I did four years at the Botanic Garden’s best four years of my career, was wonderful working with all these amazing people, experiencing all aspects of the amenity horticulture industry. I then moved off and I worked for four years at Sydney University, another fantastic experience. I spent a few years at Centennial Park as well again, and then I back to the Botanic Gardens and I’ve been lucky enough to come back in the role I’m currently in. So, I’ve been very lucky in the places I’ve worked.

Charlie Albone:

And what did you do before horticulture?

David Laughlin:

I was in construction and civil engineering before, so it was a pretty substantial career change, but I figured that that that was, as you can guess, I’m not originally from Australia, so when I was back in Ireland, I was pretty much in the construction industry, which was booming back then. But then, when we made the move to Australia 20 years ago, decided I’ll try something different. And my father always had an amazing garden, and was a wonderful gardener. So I always had a great interest in horticulture and gardening. But when I was in Ireland, it never really dawned on me to actually do it as a career. And it was only when I came here that I decided to follow my passion, I guess.

Charlie Albone:

Well, Sydney is the perfect climate to be working in horticulture and working at the Botanic Gardens. I mean, you must have felt like you died and gone to heaven.

David Laughlin:

I did. I’ve never been more nervous in all my life than the day I had my interview for the apprenticeship. It was just, I just so much wanted to work here. And it was such a great opportunity. And luckily, they took pity on me, and gave me a job.

Charlie Albone:

When you’re designing a space, I always have to ask the client how much maintenance can you give the garden, or how much maintenance do you actually want to give the garden? And then you design accordingly to that. When you are dealing with a huge public space, like the Botanic Gardens that’s already up and running, how do you plan to maintain such a large space?

David Laughlin:

Look, the principles are similar in that if we’re designing a new garden, we obviously look at the resources that we can use to maintain that garden in the long run because as you know, there’s no point in designing an absolutely beautiful garden. It’s a living growing thing and then not being able to maintain it to its best. So we do look at those resources. We also look at the type of garden that we’re working with, whether it’s a current garden or a new garden, and at the Botanic Gardens, we’ve got a sort of a hierarchy of if it’s a garden that’s linked to a science research collection, then it’s a very high priority for us to maintain those plants to a very high standard because some of those plants could be rare and endangered, some could even be extinct in the wild. So those have a huge value.

David Laughlin:

We also have conservation gardens as well, which are similar, but then we have gardens that our education teams use. We get thousands and thousands of children in yearly to do courses and complete their education at the Botanic Gardens. And then we’ve got our horticultural gardens, which are basically those beautiful gardens that everyone comes and enjoys. So, there’s sort of a hierarchy and we work out our maintenance needs based on obviously the needs of the plant, but also the importance of the collections.

Charlie Albone:

So, I guess the home gardener could prioritize what’s important to them, and that’s one way they could work out their maintenance schedule, I guess.

David Laughlin:

They should. And like one thing I would say, the gardens are to be enjoyed whether you’re working in them, or you’re just sitting, having a glass of wine at the end of the day in your garden. So, it’s grow what you want to grow, and grow what obviously you have the time to look after, and maintain is really important.

Charlie Albone:

Have you noticed a shift in the plants you’re growing at the Botanic Gardens to a more drought tolerant varieties, or are you sort of trying to show the wide variety of things that you can grow in Sydney?

David Laughlin:

Look, we are trialing plants at the moment. We have a pretty extensive trial garden, which we trial new varieties into the market. And yeah, we’re finding like Sydney’s climate is, it has certainly got warmer and sometimes the weather is getting more extreme and that can also be drought, or we can have a year like this spring where we’re actually getting quite a considerable amount of rain. Something I would say that’s vitally important is drainage. So, if we have good drainage in our soil, most of those drought tolerant plants won’t complain whenever they get rain, as long as the water’s not sitting around the root zones. But we are looking, we do push the boundaries quite a bit with plant plants’ tolerance for Sydney’s climate and as you said earlier, it’s an amazing climate to grow plants. Like we can grow such a huge range of plants from all around the world. And with Sydney’s really quite benign winters and in the summers, there’s a few days whenever it does get away, but beyond the limits, but mostly the summers are pretty nice in Sydney.

Charlie Albone:

Especially for us English and Irish. Yeah.

David Laughlin:

Yeah. Well, that’s true. Yeah. 20 years ago when I first arrived, I thought this is where, what have I done? I’ve arrived in Sahara desert.

Charlie Albone:

Yeah. I think it’s drainage is so overlooked when it comes to plants or plants like water.

David Laughlin:

Yeah.

Charlie Albone:

Some plants just don’t like water sitting around their roots. Rosemary is a great example of that, you know?

David Laughlin:

Yeah.

Charlie Albone:

It will thrive if you give it lots of water, as long as the water gets away from its roots.

David Laughlin:

Exactly. And that’s key. And I hit that sort of, that zero fight term where they talk about plants, like they almost don’t need water every living element. Like water is the most important element. It’s plants that don’t like a wet, constantly wet root zone that’s yeah. But they do need water.

Charlie Albone:

So, how do professionals plan and prepare for maintenance, like gives it a week to week process? Are there elements that are set in a diary such as tree pruning, fertilizing, or do you just make it up as you go along because things change from year to year?

David Laughlin:

Look, it’s a very planned process, generally where there’s certain key events that happen at certain times of the year like the big one is we do our winter [inaudible] in July, we just do our [inaudible] in July. And Sydney, not such a big deal because usually the idea of doing it in July is that we give it the [inaudible] and then after the last frosts, we don’t really get frost on the Harbor here, but we still do that in July. We know that certain events are going to happen at certain times a year. Like one that’s a big one frost as well is we know that the [inaudible] is going to start producing its mushrooms in June. So we keep an eye for those mushrooms and our horticulture just report back if there’s any new outbreaks of what is a quite a destructive disease and unfortunately, a disease that we do have here at the Botanic Gardens.

David Laughlin:

So there’s things they got. Yeah. And there’s certain tree printing events that happen. As you say, there’s other pruning fertilizing events. We look out for certain pests diseases at certain times of the year so we can treat those at certain life cycles. Sometimes you can treat something and you don’t actually have to go particularly harsh with a chemical if you get it at the right time and get it under control at the right time. So, there’s a lot of that. But then also, there’s weekly tasks that in the growing season, we just do weekly, such as watering, weeding, those sorts of tasks. And then there’s yeah, the more sort of, I guess, seasonal tasks that are our big task that we have to plan for and, plan a number of people to come in and help the horticultures in the section with.

Charlie Albone:

Yeah. So, I mean, in the home garden I sort of work from the canopy down, I guess the trees aren’t every year I do pruning, but your hedges, you start on the tall hedges and you work down so the debris kind of works down. You’re only cleaning up once. Is that something you try and implement in such a big spaces of the Botanic Gardens, or is it sort of more focused on individual jobs and individual garden beds?

David Laughlin:

Oh, look, we do try to plan those jobs out because we also work in a public space. And for things like hedge pruning, we’ll only have a very small area that’s fenced off so the public can’t get into the, I guess, the danger zone. So, we do try to clean up as we go along, and yeah, you’re right, pruning from the top down so there’s less mess and it’s one cleanup and making sure that there’s not those ugly clippings on top of the hedge, and stuff like that, which is a [inaudible] of mine so to say. But working in a public space is a big difference for us because planning our jobs as well at certain times, our green keepers certainly do most of their edging with the whipper snippers in that first thing in the morning, whenever it’s less busy and they certainly would never dream of doing a lawn at lunchtime. Also the noise factor for, people come out to sit down, and have their lunch in a nice, peaceful, quiet environment.

David Laughlin:

They don’t want the chainsaws going from the [inaudible] or the whipper snippers and mowers buzzing around them. So, we have to think about a lot of those aspects at the Botanic Gardens.

Charlie Albone:

Yeah. I guess it applies to annoying neighbors that complain as well. You need to work out when they’re out to mow your lawn. You touched on the [inaudible] issue you’ve got it. How much of the pest and disease maintenance program is sort of organic based, and how much is chemical based? Because I guess when you are working with so many people that come into the garden, you’ve got to be quite sensitive with the way you use chemicals.

David Laughlin:

Yeah, we do. And we do try to… We sort of, I guess we reach for the chemical bottle as the last resort, and as part of our integrated pest management program. So, we use a lot of biological controls, particularly in our rose garden. So, we release various insects that are going to eat the insects that we don’t want. And again, we try to balance that when we release them, there’s something for them to eat. But the pest hasn’t got out of control. We also like for weed switch, I guess weed tech as a pest. We’ve recently trialed a [inaudible] and it’s still under trials, so we’re hopeful that that may be another thing, another area where we reduce our reliance on chemical controls.

Charlie Albone:

Yes.

David Laughlin:

And we also, obviously we do physical controls and just observation, and knowing when to actually control the pest or disease at the optimum time, which means if we get it at a certain… If it’s a pest such as Lily caterpillar, if we get it at a certain stage and it’s life cycle, we may be able to use a biological control, but if we miss that very small window and it’s gone to a more adults cycle, then we may actually have to unfortunately use a chemical control. So, there’s a lot of that stuff that are… Our horticultures are very skilled in that area.

Charlie Albone:

Yeah. I mean, last resort is chemicals, but sometimes you just have to use them. I think it’s, as long as you’re using them properly, then it’s sort of, it’s all part of an integrated pest management system as you said. I found with weeding, when I realized that weeding will never, ever, ever be finished, then it actually becomes a job that can be quite enjoyable. You can use it as meditation, sort of zone out. It doesn’t matter if the kids come and bother you because you don’t get it finished, but you’re never going to get it finished. So, but then, I don’t have the world’s tourism coming to my garden and having a look at it like you do with yours.

David Laughlin:

Weeds are the being of our existence in many ways. And I always remember back to my days in [inaudible] and the teacher always said, “Look, if you haven’t got time to weed, at least pull the flower head off and don’t let them it see.”

Charlie Albone:

Yes. Yeah, absolutely. I mean, part of maintenance, is planning for future projects. The Botanic Gardens has got an amazing display of meadow flowers. And I know that because I spoke to you and I got the supplier of the seeds and I’ve done them at my house. But when it comes to bringing in new projects to the Botanic Gardens, how do you decide when you’re going to do that? Because some of them can be quite labor intensive. I mean, with mine, it’s laying the seed properly, keeping the water on top of it, keeping on top of the weeds before it sort of establishes, and it can become quite labor intensive, which I can imagine would be one of the hardest things to manage in the Botanic Gardens, the amount of things you have to do with the labor you’ve got. So, how do you plan a new project into your maintenance schedule?

David Laughlin:

Yeah, look, we certainly look at those resources and the metal, as you mentioned, it’s probably the most popular thing in the Botanic Gardens at the moment. And it has turned out to be an amazing project. So, during that planning process, we certainly planned all the seed mixes that we were going to use. We planned the weed eradication, which for the first couple of years actually didn’t work that well. We had a couple of pretty disastrous metals that were basically looked like an [inaudible] that had just been, that that go crazy for a season. But eventually, we got on top of the weeds and we got the seed mixes right. And we got the soil preparation, right. And the time to slash, and now the metal is, I wouldn’t say it’s self-sustaining, it still requires a fair bit of work, but that maintenance and that pressure on the team has reduced down quite significantly with the metal.

David Laughlin:

So, sometimes that’s a balance where establishing the garden is quite labor intensive, but once we get it established and to a point where the plants are out competing the weeds and various other aspects, there’s not as much water required and whatnot, we can then start to manage it. But, yeah, you’re right. We only have a certain amount of resources in the Botanic Gardens to actually maintain the plants. And there’s certain garden beds in the Botanic Gardens that are they may be mass planted with clivias and plants like that. But those plants are not the most exciting plants in the world, but our horticulture just may only have to visit that garden once a month. Whereas, a garden like the [inaudible], the horticulture just is in that garden working every day. So, we do have to have a balance of gardens that are still aesthetically pleasing, but-

Charlie Albone:

Yeah. That’s a good tip, isn’t it? I guess, for your main areas of impact, have a bit more high maintenance. And for those areas that are less conspicuous, I guess, you can mass plant. It still looks nice, but it’s not going to be an amazing feature of your garden.

David Laughlin:

Yeah. Yeah. And picking the plants that are going to be basically I compete the weeds and the plants that you don’t want to grow is key. And yeah, those plants with really fibrous root systems that basically dominate the growing area. They’re actually really useful plants to have in the garden.

Charlie Albone:

Absolutely. What tools do you think every home gardener needs, and what professional tools do you think home gardeners could use more? I mean, and I know everyone says you need a good pair of [inaudible], but is there any other really good tools you can recommend?

David Laughlin:

Oh, look, yeah, look, most garden… Unless it’s a very, very small garden, I would recommend having a few, either preferably electric or petrol tools, things like blowers, and whipper snippers. Obviously if you’ve got a lawn, you need lawn mower. But, pole printers, depending on if you’ve got a lot of trees, and you actually need to do some pruning at height, pole printers are very useful majors. As I mentioned, electrical, we’re trying to move towards more battery operated power equipment. And not only is it, it’s a lot cleaner, it’s a lot quieter, particularly in the public environment, but it’s just, it’s the way of the future, I think the way we’re heading. But there’s a lot of hand tools also that the home gardener needs.

David Laughlin:

And you mentioned [inaudible] and I’m going to go back on the [inaudible] thing because it is the tool that you are going to use most. So, if you’re going to invest in a quality product for your garden, buy a good pair of [inaudible] because they will last you a lifetime if you look after them. If you buy a $5 pair, they’ll last you a month and you’re out to buy a dollar pair. So, I definitely buy a good-

Charlie Albone:

I don’t think you’ll find a gardener telling you, you don’t need a good pair of [inaudible].

David Laughlin:

Yeah, exactly.

Charlie Albone:

Absolutely. Yeah.

David Laughlin:

But there’s a host of others. All the hand tools, your spades, forks, rakes, your hand shears, all those things. Bins and tarps, things to put, you do a lot of… You produce a lot of weeds, you do a lot of pruning, so you need something to clean up and keep things in a really, a good tool bag or bucket to keep your hand tools in, so they’re not scattered all over the place. And again-

Charlie Albone:

Do you… Sorry-

David Laughlin:

I’m sorry.

Charlie Albone:

… keep going.

David Laughlin:

No, I was just going to say, and again, something to maintain your tools as well. Sharpening stones, oil rags, all that stuff to keep them in good order.

Charlie Albone:

Do you do lots of composting at the Botanic Gardens? Because you have a huge amount of green waste you would produce.

David Laughlin:

We send all our compost offsite, so we don’t, unfortunately we don’t compost onsite and that’s just basically because of space, we actually don’t have the space to create compost. But we do send all our green waste does go offsite and does get turned into compost and quite a bit of it comes back again into the garden.

Charlie Albone:

Yeah. What common mistakes do you see gardeners doing in, not just in the Botanic Gardens, but sort of in the home garden? What sort of things do you pick up on?

David Laughlin:

Oh look you, well, quite often you see basically the most important thing to do when you first get a garden, whether it’s at the Botanic Gardens, developing a new collection of plants, is look at your site, know where the sun is, know where the shade is, know what the soil conditions are. Do a few basic soil tests like pH test and a texture test. And they’re not difficult to do. If you have never gardened before, you will be able to find a clip on YouTube. It’ll show you how to do a texture test and you can go and buy a pH test. So get those basic, know what your soil is. And then pick plants that are going to grow well in your environment. And for Sydney here, we always think, “Oh, natives. Natives are going to do well,” but Australia’s a big country. Australia’s a huge country. So not all native plants are going to do well in Sydney.

David Laughlin:

And we’d find that in Sydney, plants from the Southwestern United States, some of the Prairie plants do a lot better than plants from Western Australia that can’t handle our humidity and summer, or you certainly wouldn’t be growing plants from Darwin, that are-

Charlie Albone:

No, absolutely.

David Laughlin:

… highly tropical. So-

Charlie Albone:

It’s about getting the right plant for the right spot. Isn’t it?

David Laughlin:

It is. And if you just… It’s interesting, you look at other parts of the world that have very similar climates to the area that you live in, and there’s a range of plants that you’ll be able to find that will be very happy in your climate.

Charlie Albone:

What do you think are the best low maintenance plants that give you that high impact?

David Laughlin:

Oh, look, there’s a range of plants like that. As I mentioned, the Prairie plants, [inaudible], I think [inaudible] are hugely underused, and they flower forever and they’ve got those big Daisy flowers that everybody loves. So, they’re particularly a favorite of mine. But some of the kangaroo paws available, particularly some of the landscape varieties, like big reds been around for you years, but it’s just an amazing plant. It just keeps flowering and it does give you a huge amount of impact, Lamonia-

Charlie Albone:

How do you find it with the black spot in humidity?

David Laughlin:

I find big reds pretty good for black spot, it’s not… There’s another one called landscape gold, and there’s a Kings park Federation special, I think it’s called. Those three don’t tend to get the black spot quite as bad. Some the smaller varieties with the amazing flowers, I would treat them as annuals more than a biannual because they will eventually succumb to black spot, but they are wonderful annual plants to use. So yeah, kangaroo paws, a lot of breeding’s been done on kangaroo paws, and there’s just such an amazing range out there today.

Charlie Albone:

Yeah. I found sort of when they finish flowering, not just to remove the flower spike, but the leaves around that flower spike. So, you have a really thinned out plant, but it sort of increases the airflow.

David Laughlin:

Yeah. Yeah. That’s very important.

Charlie Albone:

Yeah. Yeah. So, what can the home gardener take from someone who looks after one of the most prestigious gardens in the whole world?

David Laughlin:

Well, thank you very much. Yeah. Look, I guess, the one thing I always say to everyone is, I’ve killed many plants in my career, and I think just about every horticulturalist has. So, if you start off gardening and you find that you bring this beautiful plant home from the nursery, you plant it, and six months later it’s dead, doesn’t necessarily mean you’re a terrible gardener. It just means that you learn from that experience and you learn about the plants that are going to do well in your garden. I guess, it gets back to that and enjoy your garden, know your garden, know what your local environment’s like, know what your micro climates are like. And then really start to enjoy your garden and start off with plants that you know, and plants that are basic, take advice. And then as you get more confidence, you can start experimenting. You can start developing your garden. But the most important thing is to enjoy it. If your garden becomes a chore, and you hit going out to do the gardening, then there’s something wrong that should be an enjoyable experience.

Charlie Albone:

Absolutely. I think you learn a lot. I mean, like you, I’ve killed a lot of plants in my time, but you learn a lot from the way you kill plants. They tell you what they need. If it’s water, if it’s too much sun, and the more you kill, the more you learn that sort of stuff. And it just can only improve your gardening, I guess.

David Laughlin:

Yeah. No, that’s very true. Just try not to keep making the same mistake over and over again. I guess.

Charlie Albone:

Exactly.

David Laughlin:

That’s a big thing.

Charlie Albone:

Yeah. Yeah. What’s the old saying? It is… I forget. Anyway, so, your garden. Is it like the painters house that’s not finished painting? Is it the plumber’s house that’s got terrible pipe work? Or is it sort of looked after to perfection? Like the Botanic Gardens are?

David Laughlin:

I wouldn’t say, if you ask my partner, she would definitely say it’s not perfection by any means, but it’s very small, so I’ve got that advantage. I’ve got a little courtyard and I’ve got a green wall, which usually at this time of the year starts to look quite good because I do a better of renovations on it coming to spring. And then by the end of winter, it’s looking a little bit tatty and I’m getting complaints. But yeah, it could be better.

Charlie Albone:

Is it like the green wall in The Calyx? Because that’s very impressive at the Botanic Gardens.

David Laughlin:

It is. It’s a little bit smaller than the one, The Calyx.

Charlie Albone:

Yeah, well you’d hope so.

David Laughlin:

But no, the one of The Calyx it’s… We use that wall to basically paint pictures. My green walls, a bit more natural looking and it’s a bit more perennial as well, because I cannot afford to keep replacing the plants at the rate that we do in The Calyx.

Charlie Albone:

But is it the same system of pots clicked onto the wall?

David Laughlin:

Yeah.

Charlie Albone:

Or is it a, yeah-

David Laughlin:

Yeah, it is that system. Yeah. It’s just a-

Charlie Albone:

It’s amazing display.

David Laughlin:

It is. And it’s a wonderful way to grow plants, particularly obviously if you’re you’re short of space and you can have quite a few extra square meters of planted area. Yeah. And you soon learn that once you put up your green wall and then you go to buy the plants to fill it, you realize how many plants fit on a green wall because-

Charlie Albone:

Yeah, absolutely.

David Laughlin:

It’s a quite an expensive exercise.

Charlie Albone:

It can be. I think I did one system that was 55 plants, a square meter. So it’s just, that can really get up there. Can’t it?

David Laughlin:

It can. But it’s worth it. They do look absolutely spectacular.

Charlie Albone:

Yeah. They give you high impact and they really don’t take up a footprint so, they’re a great addition to the garden. But David, thank you so much for your time, I do really appreciate it. You maintain, like I said, one of the best gardens in the world, and I do appreciate your knowledge. Thank you very much.

David Laughlin:

No, thank you very much, Charlie. It was a pleasure.

Charlie Albone:

Now, it is time for some community questions and we’ve got a couple of complex ones this week. Rosemary asks, that’s a nice name. Rosemary. “I have a Japanese Camillia, Cape Jasmine, and a Chinese westeria plant that I need to move in my garden. They’re currently in a full sun location and thriving. However, due to renovations, I need to transplant all three to another full sun location. So my questions are, when is the best time of year to do this?” Well, that is simple. It needs to be done in winter. If you’re trying to do it in summer, these plants are not going to do very well. So, winter is the best time, especially when they’re dormant. “How do I get the new location ready so they continue to thrive?” So, soil preparation is key here. I would rip through the soil, try and get as much air into it, try and get as much compost into it as possible.

Charlie Albone:

That way the new roots are going to find it easy to penetrate out into the soil. And with the addition of compost, it’s going to hold onto water and nutrient it’s for longer, and you have a better chance of success. And the last part of this question is, “Is there one critical element to getting a successful transplant?” And there is, and this is all about the root bowl. You need to get as many roots as you possibly can for your plant. So, dig the hole around the plant, as big as you possibly can, and try and maintain as much soil around the roots as possible, because that’s going to protect them. They’re not going to dry out and they’ll continue to grow.

Charlie Albone:

Margo has just asked, “I love listening to your podcast, That’s How We Grow. Loved it. Very informative.” Thank you, Margo. The check is in the mail. But the question is, “I put a new turf last year and suddenly have a patchy lawn. I saw a grub which I think is going to town all over my backyard. What is the best way to treat this? And does it require once off or every week treatment?” So you may possibly have a lawn grub. Now what these do is they eat the roots of the plant. And by the time you notice it on top, it’s far too late, everything’s been eating underneath and you’re going to get a patchy lawn. So, there is a lawn grub insecticide you can get, which you apply to your lawn and it kills the bug.

Charlie Albone:

Now you want to be careful with these. You want to use it as little as possible because you want to maintain as much good bacteria, and good insects in the soil whilst you’re trying to kill off this bug. So, I would use it once, maybe twice, but I probably wouldn’t use it more than that. Now, do you have a gardening question? You’d like me to answer, send me an email at charlie@stihl.com.au.

Charlie Albone:

I really enjoyed speaking with David Laughlin today. He has a wealth of knowledge and he has a truly envious job working at the Sydney Botanic Gardens. But what did we learn from him today? Well, I learned that drainage is key. All plants love water, but you need to work out the ones that just don’t like having water around their roots all the time. I found that chemicals can be used, but only as a last resort. There is a plethora of attacks you can make on insects and bugs in your garden that don’t contain chemicals. So try and exhaust those first, before you move onto the sprays. I also learned that even the best gardeners kill plants. But what you need to remember is you have to learn from your mistakes.

Charlie Albone:

Well, thanks for listening to That’s How We Grow in partnership with Steel Garden Power Tools. Do you need the power tools to take on any garden challenge, go to the stihl website or head to your local stihl dealer today. You can find us on Instagram at stihl_AU, and you can follow me on Instagram as well, charlie_albone. On our next episode, we’re going to be speaking with the acclaim landscape designer and contractor, Michael Bates. Michael is a great friend of mine, and he’s an incredible garden designer too. We’re going to be discussing garden planning and design, how to learn and work with your landscape, and how to change what you dislike in your garden. Don’t forget to check out stihl’s blog with plenty of great gardening advice, tips, and tricks. I’m Charlie Albone, and thanks for listening. Until next time. Goodbye.

Listen to the audio recording of this podcast here.